GOOD POSTURE: A State of Relaxation

What is Posture?

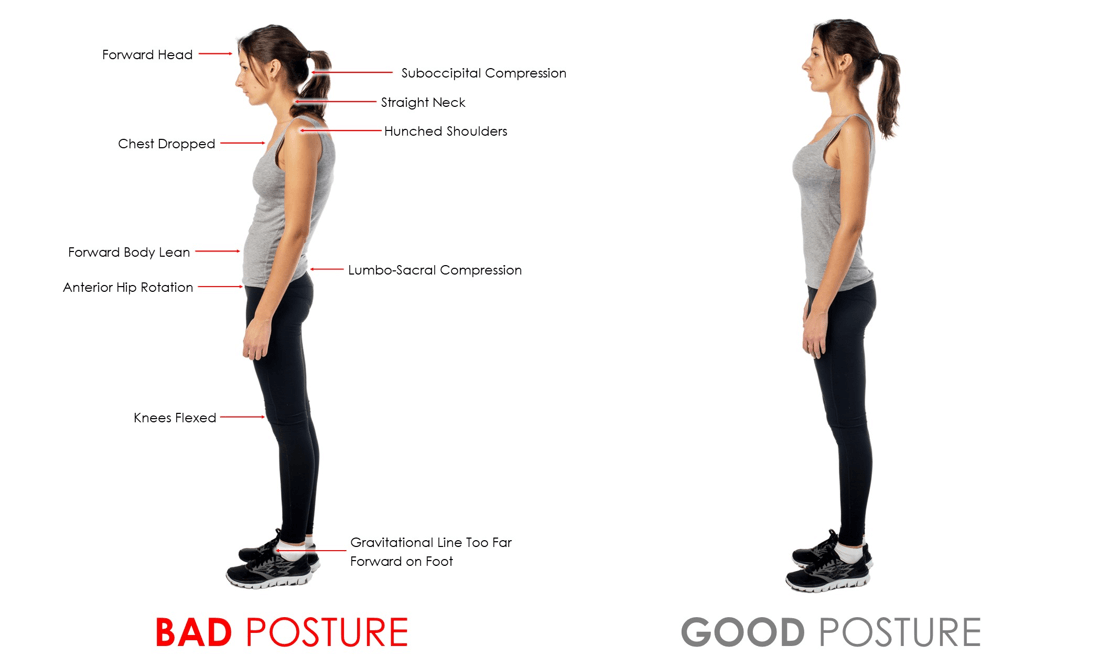

Do you ever notice when you see people with good posture? They walk erect, their heads lifted, shoulders back, their arms swing evenly, and they move with a simple, efficient gait. Unfortunately, most of us have some structural imbalance that causes us to alter our posture. Many people think that by stiffening their back to stand up straight, they are correcting their posture but the tension in their spine will reflect in other places. In actuality, correct posture is a state of relaxation.

Posture is the position in which we hold our bodies while standing, sitting, or lying down. Good posture is the correct alignment of our body, held together by ligaments and supported by the right balance of muscular tension. Poor posture is misalignment of our structure associated with stress on ligaments and an imbalance in muscular tension.

Poor posture usually starts at the core. When the pelvic ligaments become stressed, the muscles then activate to pull the body into a position that removes stress from the sprained ligaments. Unfortunately, this altered position causes misalignment in other parts of our body.

Most often, deviations from good posture can be seen in a person’s gait. While walking, look at how they swing their arms or move their feet. Their shoulders should be relaxed, and their arms should swing evenly front to back, with an even space between their hands and body. Their feet should be pointed forward and steps should be evenly spaced. We don’t see this very often.

What Causes Poor Posture?

It often begins with our core, the pelvis. It is made up of two hip bones and the sacrum, which contain three joints, the two sacroiliac joints and the symphysis pubis. The greatest bulk of our muscular mass attaches directly to these three bones. Like all joints, the muscles that attach to the bones that make up the pelvis move these three bones throughout their range of motion. Also, as in all joints, when the ligaments that tie the bones together are injured, the muscles alter their movement patterns to protect the injured ligaments.

A simple example is the knee. When knee ligaments are injured, the leg and pelvic muscles alter their pattern to remove stress from the damaged tissue, and we limp. Because the knee is large relative to the size of the muscles that move it, the muscular reaction is large and very noticeable. The same thing happens in the pelvis, the difference is in the subtlety and magnitude of the muscular reaction. Because the reaction is spread throughout most of the muscular mass of the body, we don’t notice it as much, but it causes widespread postural alterations.

If we think of our body as a contiguous series of shock absorbers, the pelvis is our core, and the sacroiliac ligaments are at the center of the core, holding it together. Almost every movement we make, whether it be bending, lifting or twisting, picking something up, or even walking, transfers force through our core. The pelvic ligaments interpret incoming forces and regulate the muscles to ensure smooth coordinated movement from the core outward. When injured, the ligaments cause the muscles to alter their movement pattern to avoid transferring force through the damaged portion of the core ligaments. We may look at it as a whole-body limp that can be very subtle and difficult to detect, yet it is evident if we know where to look, posture.

With injury, the ligaments that support our core become weak. The large mass of muscles that attach to the pelvis (from the head to the knees) reacts to hold our core together, which results in a common pattern of poor posture. This is why muscle tension is a sign of poor posture and why simply correcting posture releases tension and helps the body to relax.

Instead of standing erect and balanced, we find that we are “falling into ourselves.” The pelvis tilts anteriorly, the hip socket (acetabulum) rotates out of normal position, and the feet rotate outward, which leads to overpronation. The lumbar spine may either follow the anteriorly rotated pelvis by increasing the lumbar lordosis or, less often, the structure may try to compensate for the anteriorly rotated pelvis by straightening directly above L3; in either case, there will be compressive stress at both the thoraco-lumbar and lumbo-sacral areas. The compression is reflected by an equal and opposite stress at the cervical spine (think of twisting a towel in your hands; when you twist one end, the other end will also twist). All of these structural shifts are due to the muscles adapting to the injured core ligaments. They are subtle but persistent. Eventually, poor posture results, which puts more stress on other ligaments in the kinetic chain, compounding the disorder.

Correcting posture

There are two ways to counter this adaptation pattern. The simplest is to make postural corrections by learning what correct posture looks like and shifting your body toward it. Follow these checkpoints in any order because they are all part of a single pattern.

- First of all, relax; don’t try too hard.

- Simply stand tall.

- Tuck your chin in slightly so that you feel a slight stretch at the base of your skull. Think of a string lifting you from the top of your head.

- Keep your head level.

- At the same time, lift your sternum up slightly so that you feel a slight widening of your chest. Be aware of your chest; it should not lift more than slightly, because anything more is caused by activation of anterior neck muscles which will straighten your neck and spine improperly.

- With your mouth closed, your lower jaw should move forwards.

- Your tongue should rest at your upper palate behind, but not touching, your front teeth.

- As your chest lifts, your shoulders should roll slightly backward in their sockets.

- Your hands will rotate slightly outward.

- Rotate your pelvis backward into neutral tilt.

- Your feet should be pointed straight ahead with your weight centered just in front of each ankle.

- Breathing should come from your belly as your diaphragm becomes more involved in pulling and pushing air through your lungs

Wall Exercise: To become familiar with correct posture, stand against a wall with your buttocks and shoulders touching the wall. Keep your chin tucked in and move your head backward until it touches the wall. The back of your hands should touch the wall. Keep your knees locked, but not hyperextended, and bring your heels as close to the wall as comfortable. Gently try flattening your lower back to the wall; as this happens, you should feel a stretch of your back and neck muscles. As you improve, your back will flatten more easily. Hold this position and review the checkpoints above. Then step off and try to maintain that posture.

- As you move, you should feel your shoulder muscles relax as your upper arms drop into their sockets better and your arms swing more naturally.

- Your shoulders should follow, moving alternately forward and backward with each step.

- Your hands should be equidistant from your sides, with palms facing your body.

- All in all, you should feel more erect, more relaxed, and move more effortlessly.

The other way to counter poor posture is to stabilize your core is by healing your sacroiliac joint. There are many exercises and treatments that are promoted to stabilize the core, but they are all aimed at stabilizing the imbalanced muscles, which are actually only symptomatic to the core ligament instability. Treating the muscles will most likely give pain relief, and some people are satisfied with that. However, the only way to truly balance the pull of the muscles on the structure is by removing the stress on the sacroiliac ligaments. This can be done temporarily with a proper sacroiliac belt. But the only way to permanently heal the sacroiliac ligaments is by Supine Pelvic Blocking, (aka Sacro Occipital Technic’s Category II procedure).

For those of you who are familiar with the Musculoskeletal Integration Theory, you may recognize the pattern that develops from the Sacroiliac Nutation Lesion as the same pattern that we see with poor posture. The pelvis rotates anteriorly and shifts to one side, the spine rotates and laterally flexes to the high hip side, the shoulder is usually lower on the high hip side, and a rib hump forms on the low hip side. As the head shifts forward, the cervical and upper lumbar spine straighten, with concurrent compression at the occipital-cervical and lumbo-sacral areas. The Musculoskeletal Integration Theory explains how this pattern develops, from the initial mechanisms of injury, to ligament sprain, to muscular compensation patterns, to structural compensations that are expressed as poor posture. Finally, it ties this pattern to many chronic, painful musculoskeletal syndromes throughout the body.